At eight years old I couldn’t imagine what would become of me. I had watched my dad walk through a window, attempting to reach a blinding light he believed was God. I had seen sheriff’s deputies hie him away in a patrol car, had seen my mother weeping, had wandered through our four-room house wide-eyed and mute until I, book in hand, squeezed myself behind the bed I shared with my sister.

The story was the life of George Washington Carver, who was like me a person to whom things had happened but whom had survived, poor Carver without either parent and without agency.

I did not know when my father would return, if ever, and I tried to overlook the worry in my mother’s eyes and not ask her questions that made her scared. I thought about The Boxcar Children, a book my teacher was reading aloud to my class at school, about four children who lost both parents and lived alone in an abandoned boxcar in the woods. I knew things had ended well for those kids.

Somewhere in the grim months of my father’s first nervous breakdown—which became a black hole in my memory, a void of bleak uncertainty and maybe even despair—I learned what could save me and, by extension, save all of us.

I know nothing more powerful than the power of stories. I say this again: They saved my life.

Immersion in story when I was most impressionable drove home what my father already demanded of his children before a supernova sucked him away, that we understand the art of empathy. Stories of the “other” are the scaffolding of empathy, and in my father’s paradigm, empathy required action. For example, a heron struck on the highway required that my father splint its broken wing. An elderly man who appeared at my dad’s junkyard on Christmas Day hoping to pawn tools meant gathering up a box of food. A hitchhiker needed a ride.

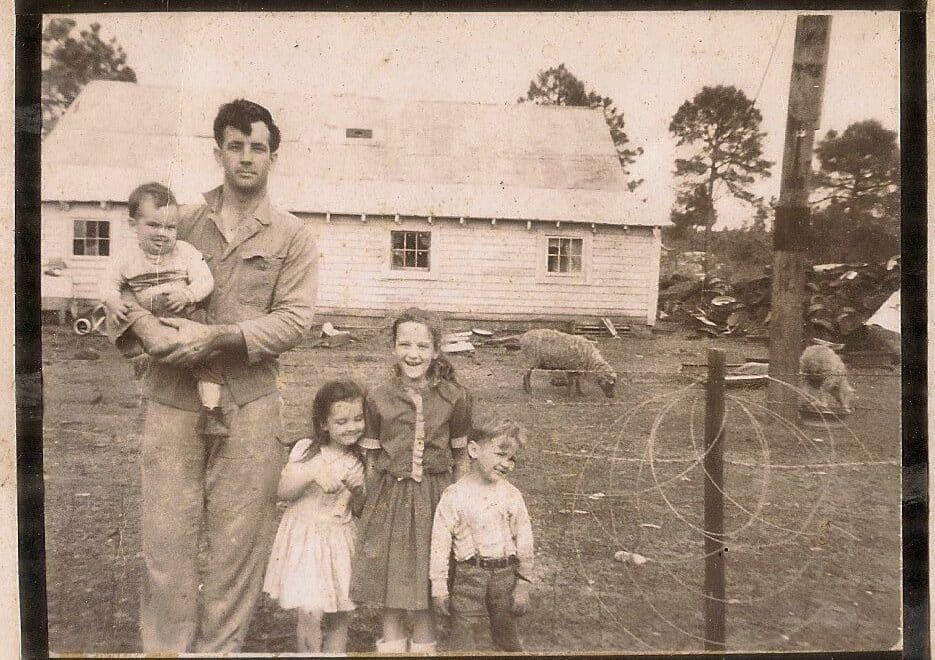

Exactly what would become of me was set in motion during those early years on a junkyard in southern Georgia, with my father locked away in a crazyhouse in Milledgeville and orbiting a far and bewildering side of the universe, and my mother tight-lipped, doing what had to be done.

I would become a writer of stories with hidden agendas, essentially to make the world a more empathetic place.

If the arc of time bends toward justice, stories are what push us along. I believe that the world needs stories. Human civilization depends on them. I believe that all stories matter. Your story matters. I long to know who you are, what you have seen, and what you know. Therefore, you matter. What happens to you matters.

Leave a Reply